Toward Inclusive Research: The Effect of Response Options on Gender Categorization of Faces

Elli van Berlekom, Stefan Wiens, and Marie Gustafsson Sendén

Psychology Department, Stockholm University

Abstract

Psychological research often treats gender as binary and unidimensional, even though this oversimplifies the variability of gender. In two experiments, we studied how alternative response options influence how people perceive the gender of a racially diverse set of morphed faces. Experiment 1 (N = 71) compared one-dimensional and two-dimensional scales for gender categorization. Results indicated that participants consistently used the ends of dimensional scales, resulting in highly categorical perceptions. Experiment 2 (N = 100) compared traditional binary response options with multiple categories and free-text answers. Results indicated that providing more response options than the binary (e.g., “non-binary”, “I don’t know”) made participants perceive gender as more diverse. In contrast, free-text options did not change a binary categorical perception of gender. Despite the opportunity to categorize faces beyond the binary, the predominant categorizations remained as ‘woman’ or ‘man’. We conclude that multiple response options seem to be the best way to increase perceivers’ understanding of gender beyond the binary.

Toward Inclusive Research: The Effect of Response Options on Gender Categorization of Faces

Many transgender and gender diverse people experience gender as fluid, diffuse, and outside the typical binary of women and men (Hyde et al., 2019; Richards et al., 2016a). Unlike cisgender people - who identify with their assigned gender at birth - transgender people identify with a gender different from their assigned sex at birth (Levitt & Ippolito, 2014). Moreover, many transgender people identify as nonbinary, which can be either an identity in and of itself or an umbrella term for a wide variety of gender identities other than woman or man (e.g., genderqueer, agender, genderfluid) (Monro, 2019).

Surveys and questionnaires that collect data on gender have typically used response formats that do not account for this gender diversity, for example by including only the categories woman/female and male/man as response options (Saperstein & Westbrook, 2021). This is beginning to change; it is increasingly common for studies to include response formats that are sensitive to a wide variety of gender identities, at least when collecting data on participants’ own gender identities (Hyde et al., 2019). Research on gender categorization of others, however, is still dominated by binary response options (e.g., Campanella et al., 2001; Habibi & Khurana, 2012; Jung et al., 2019). This is potentially problematic; gender categorization research needs to accurately capture the full complexity of gender; moreover, gender categorization is susceptible to influence by short-term methodological factors (Atwood et al., 2024; Thorne et al., 2015). The importance of research on gender diversity and the risk of influencing participants suggests that response formats themselves need to be examined. The aim of this research is therefore to examine two types of response formats that challenge binary gender: multidimensional scales and multiple response options beyond the binary.

Gender and Gender Categorization

To understand why response formats matter, it is important to understand the concept of gender itself. Gender is a multifaceted concept with both personal and cultural aspects (Hyde et al., 2019). The personal aspects of gender include a person’s physical body (i.e., sex) and their internal sense of gender (i.e., gender identity). Both sex and gender vary on a spectrum; sex is determined by chromosomes, hormones, and physical morphology, none of which need conform to the typical binary and gender can take an encompass an even broader range of expressions and categories. The cultural aspects of gender include beliefs about which gender categories exist, prescriptions and proscriptions for appropriate behavior for different gender categories, as well as the language available to refer to gender, including gendered pronouns and the names of gender categories (Lonergan & Palomares, 2020).

The personal and cultural aspects of gender are interconnected (Morgenroth & Ryan, 2021); cultural norms often constrain the personal aspects of gender, and, inversely, individuals’ enactments of gender may influence cultural norms over time (Butler, 1999). For example, in many cultures that conceive of gender as binary, there are no words or few to express non-binary gender, limiting gender diverse people’s ability to know and express their identity N. Thorne et al. (2023). Additionally, the interconnection between the personal and the cultural aspects of gender suggests that inter-individual interactions are important arenas for the emergence and enforcement of gender norms. Treating someone according to the prescribed norms for a specific gender can be impactful, especially for gender diverse people: such actions can be affirming if consistent with that person’s gender identity, negating if not Fasoli et al. (2023).

Indeed, many studies suggest that gender categorization is a determining feature of social interactions (Kessler & McKenna, 1978; Liberman et al., 2017) and can activate stereotypes and associations (Freeman & Ambady, 2011). People base their gender categorizations on others’ external features Cloutier et al. (2014)) in a process that is effortless (Yang & Dunham, 2019), fast (Tomelleri & Castelli, 2012), and does not require much visual input (ref?). Indeed, based on this evidence, some have concluded that gender categorization is an automatic (Jung et al., 2019) and unavoidable feature of social interactions (Fiske, 1998).

Another feature of gender categorization is that responses display a pattern consistent with categorical perception (Campanella et al., 2001). For example, when people categorize faces that are morphed to vary on a continuum from feminine to masculine, their categorizations are exaggerated compared to the level of facial gender (Rule et al., 2012; Campanella et al., 2001; Atwood et al., 2024). This means that a 60% female morph may be categorized as a woman by closer to 80% of participants (Campanella et al., 2001). Categorical perception patterns have been observed for other domains, such as colors (blue, green) and phonemes (“ga”, “ba”) and suggest that people view stimuli that vary on a continuum as consisting of just a few categories (Simanova et al., 2016). The observation of categorical perception of gender, therefore, implies that people treat gender as a binary consisting of women and men only.

However, recent work suggests that a binary view of gender is not inevitable. For example, in one study, participants were tasked with keeping track of three people carrying out a conversation (Gallagher et al., 2025). On both implicit and explicit indices of gender categorization, younger participants and participants with personal experience of gender diversity were less likely than other participants to categorize conversationalists by gender [Gallagher et al., 2024]. Additionally, two studies have shown that categorical perception of gender can be disrupted. S. Thorne et al. (2015) reduced participants’ categorical perception by presenting faces only in the left visual field. These stimuli were processed by the right brain hemisphere, implying that only the left brain hemisphere displayed categorical perception of gender. Moreover, Atwood and colleagues (2024) reduced categorical perception simply by presenting participants with a third response option beyond woman and man. The last study, in particular, suggests the importance of response formats in determining outcomes in categorization tasks.

Response Formats and Gender Categorization Beyond the Binary

Therefore, it may be troubling that research gender on categorization has largely operationalized gender using response formats that suggest that gender is binary Lindqvist et al. (2020). Two examples of such formats are gender categorization expressed as a single dimension (feminine-masculine) and as binary response options(woman/female and man/male). Both response formats imply ideas about gender: a single dimension suggests that femininity and masculinity are mutually exclusive oppositesl and binary response options suggest that those are the only gender categories that exist. It is therefore possible that binary response formats bias participants toward a binary conception of gender.

As gender is diverse, it is important to understand which types of response formats capture gender diversity. One approach is to operationalize femininity and masculinity as independent dimensions. Unlike one-dimensional treatments of gender, a two-dimensional approach does not imply that femininity and masculinity are opposites and that an increase in one necessarily entails a decrease in the other, destabilizing binary notions of gender (Liben & Bigler, 2017). Two-dimensional approaches have been used to assess gender as a psychological trait (Bem, 1974), as self-idendified categories (Saperstein & Westbrook, 2021) and as categorization of others (Wittlin et al., 2018). Moreover, at least one study found that femininity and masculinity were independent of each other (Hester et al., n.d.).

Another approach has been to broaden the response options even further Saperstein and Westbrook (2021) by including a range of response options in addition to woman/female and man/male. This approach is increasingly common for assessing participants’ own gender identity (Li et al, 2024., Saperstein et al.) and has been used in a handful of studies of gender categorization of others (van Berlekom et al., 2024; Weissflog et al, 2024). Additionally, Lindqvist et al. (2020) suggested that the most sensitive measure for self-categorization would be an open text entry where participants can fill in their gender in an open-ended format. The free text response has the advantage of being completely unconstrained, allowing participants to enter any category.

These approaches may imply that gender is visible from appearance. However, because gender identity is an internal felt sense of self is and not determined by sex, appearance is not always a reliable indicator of gender identity. In real-world contexts, therefore, relying on external attributes to categorize gender can lead to miscategorization. Therefore, in situations where misgendering might occur, it is essential to allow for an ‘I don't know’ option.”

The Present Research

Study 1 investigated the influence of dimensionality on categorical perception of gender. We compared one-dimensional and two-dimensional response formats. Study 2 investigated the influence of response option freedom on the categorization of binary and non-binary gender. We compared binary options, multiple options, and free text entry. Both studies were exploratory and did not include any preregistered hypotheses.

Study 1

Method

Participants

Swedish participants (N = 71) completed the study at the Stockholm University campus (Mage= 37.87, SDage = 14.08, Range = 18 - 73). Participants comprised 33 women, 35 men, and 2 participants who did not indicate gender (self-identified gender was measured using an open-ended text box, following Lindqvist et al., 2020). Participants were randomly allocated to one of the two response option conditions (Ncontrol = 33, Nexperimental = 38). Participants were monetarily compensated for their time (100 SEK). In accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, all participants were informed that participation was voluntary and gave written consent to participate in the study.

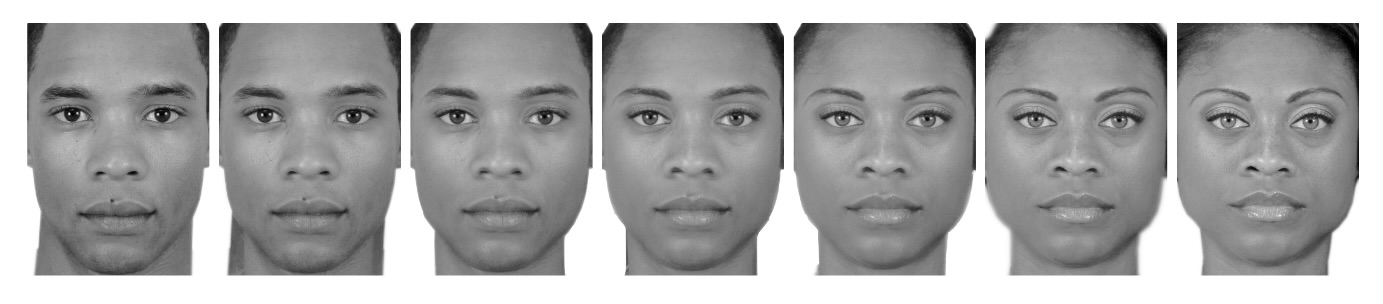

Stimuli

The experiment included Black, Asian, and White faces from the London Face Database (DeBruine & Jones, 2017) and the Chicago Face Database(Ma et al., 2015) morphed with Webmorph (DeBruine, 2018). We selected matched pairs of faces of women and men, ensuring that the women were rated at similar levels of feminine as the men were rated masculine according to the norming data (Ma et al., 2015). The morphs were made in 7 steps, from completely feminine to completely masculine. We defined facial gender as the position of the face on the morphing continuum. In other words, a 33% face was slightly masculine, a 50% face was an even mixture of the two faces, and a 100% face consisted only of the woman’s face. Because there were 18 face pairs morphed in 7 steps, the total number of faces was 126.

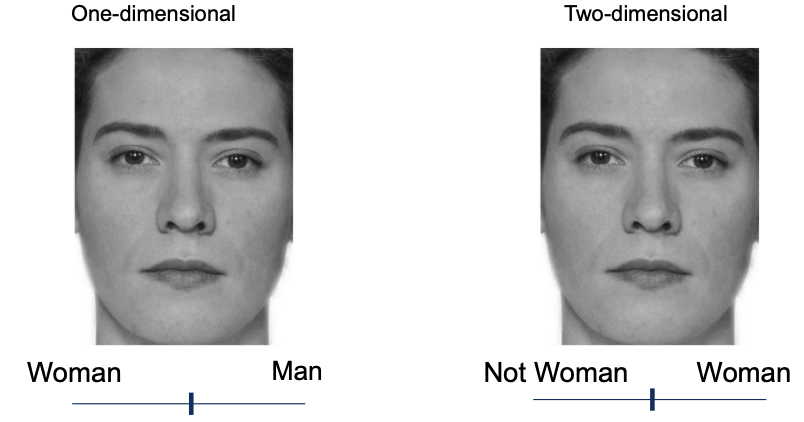

Procedure

Participants completed the experiment on a computer in a quiet room. Each trial consisted of a face accompanied by the question, “How would you gender categorize this person?”. In the one-dimensional condition, participants rated gender based on a single continuum, with the anchors marked woman and man. In the two-dimensional condition, participants rated each face once on a woman continuum (the anchors were marked not woman and woman) and once on a man continuum (anchors were marked not man and man). The separate continua were presented on different trials. For each condition the order of trials was completely randomized in both conditions (see Figure 2).

Data analysis

We used R (Version 4.2.2; R Core Team, 2022) and the R-packages brms (Version 2.18.0; Bürkner, 2017, 2018, 2021), papaja (Version 0.1.1; Aust & Barth, 2022), and tidyverse (Version 1.3.2; Wickham et al., 2019). We fit Bayesian mixed-effects models to the data to test for patterns of responses consistent with categorical perception. In all models, facial gender (0 to 100 in seven steps) and response options (one-dimensional, two-dimensional) were included as fixed effects. Additionally, all models included varying intercepts for both participants and faces and varying slopes for facial gender. We modeled the predictor facial gender as an unordered factor with seven levels corresponding to each of the seven morphing steps. This allowed us to test for non-linear patterns that would be observed under categorical perception, where changes in facial gender would be expected to have a larger effect on rated gender near the midpoint than at extreme values.

Results

We examined the relationship between ratings of woman and man in the two-dimensional condition across trials and subjects. These were highly negatively correlated (R = -0.86). Therefore, man ratings in the multiple dimensions were reverse-coded for subsequent analyses. Second, we examined whether participants responded categorically to faces (Research Question 1). Individual-level (thin lines) and group mean (thick lines) responses are visualized in Figure 3. If participants respond according to the morph level, the lines should be a straight diagonal. Instead most participants display a non-linear S-shape, and this was also the pattern of the group means. Note that in the two-dimensional condition, participants rated each face twice.

To further test whether the faces were rated categorically, we calculated the difference between the mean ratings when facial gender was 33% and 67%. If participants respond linearly, this difference should be 34. Instead, in both the one-dimensional condition (M1D = 59.58, CI1D = [53.65, 65.26]) and the two-dimensional condition (M2D = 58.75, CI2D = [52.53, 65.08]) this difference far exceeded 34 and the narrow credible intervals suggest these measures were precisely estimated. We interpret this to mean that participants responded categorically.

Finally, we tested whether the categorical perception was reduced in the two-dimension condition compared to the one-dimension condition (Research Question 2). In other words, we calculated the mean difference between 67% faces and 33% faces and then computed the difference of differences between the two conditions. The results suggested that categorical perception was not reduced by two-dimensional response options (Difference = -0.83, CI = [-5.57, 7.24], BF01= 30.47).

Discussion

Participants responded categorically when rating faces in terms of gender. Additionally, two-dimensional response options did not reduce this effect. Indeed a binary view of gender was present and participants treated womanhood and manhood as opposites even though the scale would have allowed them to be more flexible. However, this scale only implicitly challenged the binary, as no diverse gender options were present.

Study 2

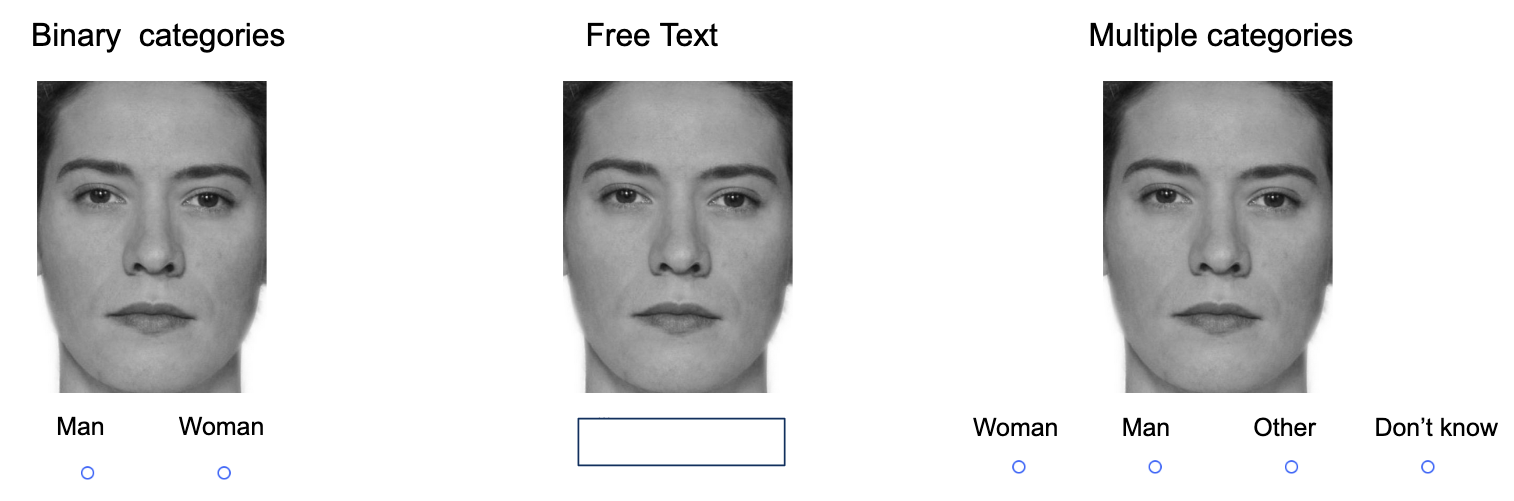

Study 2 tested a wider range of response options that explicitly challenge the gender binary. These were adapted from common ways to measure participants’ self-categorization of gender (Lindqvist et al., 2020; Saperstein & Westbrook, 2021).Subjects were randomly assigned to one of three response opotions conditions: 1) binary categories; 2) multiple categories 3) free text.

Method

Participants

Swedish participants (N = 100) took part in the study at the Stockholm University campus (Mage= 36.89, SDage = 13.69, Range = 18 - 69). Self-identified gender was measured using an open-ended text box. The final sample comprised 50 women, 47 men, and 3 participants who did not indicate gender. All participants were informed that participation was voluntary and all gave written consent to participate in the study. Participants were randomly allocated to one of the two response option conditions (Nbinary = 32, Nmultiple = 36, Nfree_text = 32). Participants were monetarily compensated for their time (100 sek).

Stimuli

The stimuli were identical to those of Study 1.

Design and Procedure

The experiment used a between-participants design. There were three conditions with different response options: binary categories, free text, and multiple categories (see Figure 4). In the binary categories condition, the response options consisted of two categories: woman and man. In the free text condition, the response options consisted of an open text box. In the multiple categories condition, the response options consisted of four categories: woman, man, other, and I don’t know.

Participants completed the experiment on a computer in a quiet room. Each trial consisted of a face accompanied by the question, “How would you gender categorize this person?” Participants categorized 126 faces according to the response options in their condition.

The outcome was responses to the categorization task. For analysis purposes,two new variables were created.

Other categorizations represented the trials where participants categorized faces as “other”. This was computed by dichotomizing the variable so other was coded as 1 and all other responses were coded as 0. In the free text condition, participants’ responses were manually coded so that other and non-binary were counted as other.

I don’t know responses represented trials where participants did not categorize any gender category. I don’t know was coded as 1 and all other responses were coded as 0. In the free text condition, participants’ responses were manually coded so that variations of unsure were counted as I don’t know.

Data analysis

Bayesian linear mixed effect models were fit to the data in study 2. These models were the same as in Study 1 apart from the outcome, which was binomial and accordingly had to be modeled as a binomial distribution.’

Results

Figure 5 illustrates the proportion of faces (y-axis) categorized according to the different conditions (different colors) at each level of facial gender (x-axis) across the three experimental conditions (separate plots). A visual inspection of Figure Figure 5 suggests that most faces were categorized as women or men. However, participants did categorize faces outside of this binary in the multiple categories condition, as Figure 5 shows, and most such categorizations were made in response to androgynous faces.

Figure 5, however, only illustrates the total number of categorizations across all participants. This obscures the fact that some participants made many categorizations beyond the binary and some made few or none at all. Figure 6 illustrates how many categorizations beyond the binary participants made. Each bar represents how many participants (y-axis) made a certain number of categorizations (x-axis). The different colors denote the different categorizations. Participants who only categorized faces as women or men are not represented in the figure. In the Free Text condition, only two participants made any other categorization than woman and man, whereas more than half did so in the Multiple Categories condition (see Figure 6 ).The Bayesian mixed effects model suggested that participants made more categorizations beyond the binary in the multiple categories condition compared to the free text condition (OR = 5.56, CI =[1.1, 27.97], BF10= 4.55).

Inspection of Figure 5 suggests that participants in multiple categories condition made fewer man categorizations than participants in the other two conditions. We tested this by examining only responses of woman or man. Figure 8 illustrates proportions of responses of women and men. Each dot represents a single participant, and the position of the dots on the y axis shows the proportion of faces that each participant categorized as man; the boxplots show median and interquartile range proportion of faces categorized as men. Overall rates of binary categorizations were similar across the three conditions (see Figure 8).

We treated the binary categories condition as the control against which the other two conditions were compared. The results suggested that the proportion of faces categorized as women was similar in the Multiple Categories and Binary Categories conditions (OR = 0.68, CI =[0.4, 1.17], BF01= 5.98). The results suggested that the proportion of faces categorized as women was the same in the Free text and Binary Categories condition (OR = 1.03, CI =[0.6, 1.78], BF01= 15.27). In sum, neither the free text nor the multiple categories condition changed the pattern of categorization of women and men compared to the binary categories condition.

Discussion

In Experiment 2, we tested how free text options and multiple categories affected participants’ responses beyond the binary. Some participants made some categorizations beyond the binary in the multiple categories condition, but virtually none did so in the free text condition. Furthermore, additional response options reduced the absolute number of faces categorized as women and men (as participants selected some of the other options) but did systematically reduce categorizations of men more than women or vice versa.

General Discussion

Across two experiments, we tested how different response options influenced gender categorization. In Study 1, we compared two-dimensional scales with one-dimensional controls. We found that participants responded categorically, and this was the case in both the control condition and the two-dimensional condition. In Study 2, we compared free text and multiple categories. We found that only multiple categories elicited beyond-binary responses. Compared to binary control, neither changed the pattern of categorizations of women and men.

The results from Study 1 are consistent with previous work on categorical perception of gender in faces (Campanella et al., 2001, 2003). Participants exhibited a categorical pattern of responses where ratings of gender were more extreme than the facial gender. This implies that participants had a conception of gender as consisting of two distinct categories. Furthermore, the two-dimensional ratings did not reduce the strength of the categorical effect. This suggests that, at least in the present sample, two-dimensional response options were not enough to reduce the binary gender norms.

This differs slightly from the results of Bem (1974), who found that measuring gender as two separate scales led participants to treat gender as less binary. Moreover, where she found that masculinity and femininity were largely unrelated, we found that ratings of woman and man were strongly correlated. This is probably accounted for by the differences in outcome measures in Bem (1974) and in our study. Bem (1974) measured gender as a psychological trait in the self, whereas we measured gender as a judgment of the gender identity of others. The latter outcome is not only determined by the response options, but also by the physical features of the faces. In other words, judging the faces of others is a different task from judging one’s own characteristics, and one of the primary differences is the increase in external stimuli and influences.

The finding from Study 2 that participants use non-binary response options is consistent with the work of Saperstein and Westbrook (2021) and Lindqvist et al. (2020), which has shown that including flexible response options allows participants to better express themselves. A recommendation from that literature is that open text boxes afford participants the greatest flexibility in their responses. In our study that flexibility was rarely used when the response options consisted of a free text. This likely reflects the difference between transgender and gender-diverse participants categorizing their own gender and cisgender participants categorizing others.

A probable explanation for the difference between free text and multiple categories in Study 2 is that the multiple categories served as a visual reminder of non-binary identity. Researchers interested in the categorization of non-binary identity should be aware that these may not spring to mind unless participants are explicitly reminded of them.

Neither free text nor multiple categories influenced the categorizations of women and men. This suggests that such inclusive response options can be suitable for investigating the categorization of women and men without skewing the results or introducing noise. This is a positive finding for researchers who are primarily interested in such categorizations but do not want to contribute to the marginalization of trans and non-binary individuals.

Overall, we recommend researchers include non-binary response options in gender categorization studies. Multiple dimensions, free text, and multiple categories and continua are all viable alternatives. If the primary research question is to investigate non-binary categorization, then multiple categories are most suitable. However, if the goal is to measure the categorization of women and men, free text or multiple categories may be equally suitable.

Limitations and future directions

One limitation of this study is the sample size. The Ns in each condition are below many of the conventional recommendations in social psychology. However, these recommendations are typically made based on the assumption of a single trial per participant. In contrast, each participant completed 126 trials in our experiment. This allows for precise detailing of the within-participant processes. As such, the present study resembles psychophysical experiments, which also feature few participants carrying out many trials. Power is often portrayed as a function of sample size, and this is true, the number of trials is also a factor in power (Judd et al., 2017). Indeed, the overall analyses included more than 8000 data points in each experiment, and the final estimates were measured with a high degree of precision. That said, we note that the generalizability of the experiment is somewhat reduced.

Another limitation of this study is that it does not account for the influence of markers of gender other than faces. Such markers include hair, clothes, and makeup and Transgender and gender diverse often use such markers to signal their gender to others. Moreover, the faces used here were not “realistic” in that they did not realistically depict gender diversity as it is often displayed in the real world. In that sense, it is possible that we underestimate the rates of people responding with one of the options beyond the binary.

Conclusion

In two studies, we tested how different response alternatives affected gender categorizations. In Study 1, participants responded categorically to the faces, both when rating gender using one-dimensional and two-dimensional scales. This suggests that participants generally had a binary conception of gender, which was not influenced by response options. In Study 2, participants were more likely to categorize faces beyond the binary when using multiple categories, including non-binary and I don’t know than when using a free text option. In comparison to self-identification questions, where open-ended responses are seen as the most inclusive alternative (Lindqvist et al., 2020), the categorization of others benefits from response options that explicitly remind participants that not all people identify as women or men.

References

Figure 1

Example of a seven-step morphing spectrum

Figure 2

Sample trial from each of the three conditions

Attaching package: 'gridExtra'The following object is masked from 'package:dplyr':

combineFigure 3

Participant level and mean ratings of faces in One-dimensiona and two-dimensional conditions

Figure 4

Sample trial from each of the three conditions

Figure 5

Gender Categorizations by Participants

Figure 6

Responses of other and I don't know across the multiple categories and free text condiitons

Figure 7

Alternative version of the previous figures

Figure 8

Participant Proportions for Categorizing Faces as Men Across Experimental Conditions